Blog

Look, I'm going to be straight with you. Most AI marketing tools are expensive. Jasper starts at $39/user/month just for basic features. Other platforms charge up to $99/month for their premium tiers. And that's before you factor in all the separate tools you need for different tasks. That's what makes American Marketing Company Marketing Tools different. At $49/month, you're getting an entire marketing department in your pocket. Not just one tool. Not just a few features. Everything. Let's break down what that $49 actually buys you: A full AI content creation suite that would normally cost $40-60/month on its own Email marketing automation that typically runs $30-50/month elsewhere Social media management tools that usually cost $25-35/month SEO optimization features that other companies charge $50+/month for Analytics and reporting that could easily set you back $30-40/month Add that up, and you're looking at $175-235 worth of marketing tools. For $49. But here's the real kicker: According to recent market analysis, businesses using AI marketing tools are seeing an average ROI increase of 37%. Think about that. If you're making $5,000 a month now, that's potentially an extra $1,850 in your pocket. From a $49 investment. "But I can just use free tools," you might be thinking. Sure, you could. You could also cut your own hair, change your own oil, and do your own taxes. But at some point, you have to ask yourself: What's your time worth? The average small business owner spends 20 hours per month on marketing tasks. With American Marketing Company Marketing Tools , our users report cutting that down to 5 hours. At even a modest $50/hour valuation of your time, that's $750 worth of time saved every month. Here's what makes this offer different: No contracts No hidden fees No "premium" features locked behind higher tiers No per-user pricing that suddenly triples your costs No complex onboarding process Just $49/month for everything. That's less than what most businesses spend on coffee for the office in a week . And unlike other platforms that make you pay extra for AI features, which can drive costs up significantly for small businesses , everything at American Marketing Company Marketing Tools is powered by AI from the ground up. Think about it this way: $49 is: Less than one tank of gas Less than a decent dinner for two Less than most monthly phone bills Less than what most competing tools charge for just one feature But unlike those expenses, this $49 is an investment that pays for itself. Often in the first week. Here's my challenge to you: Try it for one month. That's all. If you don't see at least a 2x return on that $49 investment, I'll be shocked. With the AI marketing industry growing by 38% in 2025, can you really afford to wait? The catch? There isn't one. But there is a reality: As AI technology costs rise, this $49 price point won't last forever. Lock it in now. Ready to stop wasting time and start growing your business? Visit American Marketing Company Marketing Tools and click "Subscribe." Your future self will thank you. P.S. Still on the fence? Remember this: While you're reading this, your competitors are probably already using these tools. The question isn't whether to embrace AI marketing - it's whether you'll do it before or after them. Peace - Love - Happiness ~doug h

When someone consistently accuses their spouse of infidelity despite no recent or real evidence of cheating, we're often looking at a complex psychological framework built on deep-seated insecurities and past wounds. Let's examine the psychological makeup of such an accuser. At the core of these accusations lies an intricate web of attachment issues, typically rooted in childhood experiences. The accuser often grew up in an environment where trust was broken repeatedly – perhaps by witnessing parental infidelity, experiencing abandonment, or dealing with unreliable caregivers. These early experiences created a template for future relationships: expect betrayal before it happens. The brain of a chronic accuser operates on high alert, similar to someone with post-traumatic stress disorder. Every late night at work, every friendly conversation with a colleague, every slight delay in responding to texts becomes potential evidence of infidelity. This hypervigilance stems from an overactive threat-detection system, where the brain has learned to scan constantly for signs of abandonment or betrayal. Interestingly, these accusations often serve as a self-protective mechanism. By maintaining a state of suspicion, the accuser creates an emotional shield – if they expect betrayal, they believe they can't be caught off guard by it. This defensive posture might feel safer than vulnerability, but it creates a self-fulfilling prophecy: their behavior pushes away the very person they're desperate to keep close. The accuser's thinking patterns typically show several cognitive distortions. They engage in black-and-white thinking, where small actions are categorized as either absolute loyalty or complete betrayal, with no middle ground. They also demonstrate mind reading, assuming they know their partner's thoughts and motivations without evidence. Confirmation bias plays a significant role – they seek out information that confirms their suspicions while dismissing evidence of faithfulness. Below this surface behavior often lurks profound self-esteem issues. The constant accusations might really be saying, "I don't believe I'm worthy of faithful love." This self-doubt can manifest as projection – if they have thoughts about infidelity or struggle with loyalty themselves, they might project these feelings onto their partner, finding it easier to locate these threatening feelings in someone else rather than confronting them within themselves. The accuser's relationship history typically shows a pattern of turbulent connections. Previous relationships likely ended due to similar trust issues, yet they often blame these failures entirely on their former partners. This pattern reveals an inability to engage in healthy self-reflection or take responsibility for their role in relationship dynamics. Control becomes a central theme in their behavioral repertoire. The accusations serve as a tool for controlling their partner's behavior – where they go, who they talk to, how they spend their time. This control temporarily soothes their anxiety but ultimately creates a pressure cooker environment in the relationship. Perhaps most revealing is their response to reassurance. When their partner provides evidence of faithfulness or offers genuine reassurance, the accuser might experience temporary relief, but it's quickly replaced by new doubts. This pattern suggests that the real issue isn't about gathering enough evidence of loyalty – it's about an inability to trust even when evidence is abundant. The accuser's emotional landscape is dominated by fear, shame, and anger. Fear of abandonment drives their vigilance, shame about their insecurities fuels their defensive behavior, and anger – both at themselves and their partner – creates a constant state of emotional arousal that makes rational thinking difficult. Their communication style often involves subtle manipulation tactics: guilt-tripping, emotional withdrawal, or explosive confrontations. These behaviors serve to keep their partner off-balance and defensive, creating a dynamic where the partner constantly tries to prove their innocence rather than addressing the underlying trust issues. Without intervention, this pattern typically escalates. The accuser's behavior can become increasingly controlling and obsessive, sometimes leading to monitoring their partner's phone, following them, or demanding constant updates about their whereabouts. This surveillance behavior provides short-term relief but further damages the relationship's foundation. Recovery from this pattern requires deep therapeutic work. The accuser needs to confront their attachment wounds, develop healthier coping mechanisms, and learn to tolerate the inherent vulnerability that comes with loving someone. Until they address these core issues, they're likely to repeat this pattern, either in their current relationship or in future ones. The accused partner in this dynamic faces their own psychological challenges, often experiencing what psychologists term "walking on eggshells syndrome." This constant state of defensive alertness creates a profound shift in their personality and emotional well-being over time. Initially, many accused partners respond with patience and understanding, offering reassurance and transparency in an attempt to alleviate their partner's fears. They might freely share passwords, check in frequently, and adjust their social behaviors to avoid triggering accusations. However, this accommodation gradually erodes their sense of autonomy and personal boundaries. The psychological toll on the accused manifests in various ways. They often experience heightened anxiety, depression, and a diminished sense of self-worth. Their mental energy becomes consumed by the need to document their whereabouts, explain innocent interactions, and defend against accusations, leading to cognitive exhaustion and decreased performance in other life areas. A particularly insidious effect is the phenomenon of "induced doubt," where the accused partner begins to question their own reality. The constant barrage of accusations can create a form of gaslighting effect – even though they know they're faithful, they start doubting their own behaviors and intentions. Did that friendly conversation with a coworker cross a line? Was that social media like inappropriate? This self-questioning can lead to a fragmentation of their identity and social withdrawal. The accused partner often develops their own maladaptive coping mechanisms. Some become hypervigilant about their own behavior, essentially internalizing their partner's surveillance. Others might react with increasing defensiveness or hostility, while some retreat into emotional numbness as a form of self-protection. These responses, while understandable, further deteriorate the relationship's emotional foundation. Perhaps most concerning is the gradual erosion of the accused partner's support system. Fearing their interactions might trigger accusations, they often distance themselves from friends and family, leading to social isolation. This withdrawal removes crucial external perspectives and emotional support, making it harder to maintain a balanced view of the situation or seek help when needed. The relationship itself becomes a complex system of mutual reinforcement, where both partners' coping mechanisms interact to create increasingly dysfunctional patterns. This dynamic often follows a predictable cycle that mental health professionals have termed the "accusation-defense spiral." In this spiral, the accuser's hypervigilance leads to questioning, which prompts defensive responses from their partner. These defensive responses, even when completely justified, often trigger more suspicion in the accuser's mind – "Why are they so defensive if they have nothing to hide?" This creates a feedback loop where each partner's natural responses intensify the other's problematic behaviors. The relationship gradually loses its capacity for joy and spontaneity. Simple pleasures like social gatherings, work events, or even casual conversations with others become potential minefields. The couple's emotional energy becomes so focused on managing accusations and defenses that little remains for nurturing the positive aspects of their connection. Breaking this cycle requires a multi-faceted therapeutic approach. Individual therapy for both partners is often essential – the accuser needs to address their underlying attachment trauma and develop healthier coping mechanisms, while the accused partner requires support in rebuilding their sense of self and establishing healthy boundaries. Couples therapy can then serve as a bridge, helping both partners understand their roles in the dynamic and develop new patterns of interaction. Success in treatment often depends on both partners' willingness to examine their roles without becoming defensive. The accuser must confront the painful reality that their protective mechanisms are actually causing harm, while the accused partner needs to understand how their accommodating behaviors, though well-intentioned, may enable the dysfunction to continue. Recovery typically progresses through distinct stages. The first involves creating safety and stability, often through clear boundaries and communication guidelines. The second focuses on processing underlying traumas and developing new coping skills. The final stage involves rebuilding trust and intimacy, but with new awareness and healthier patterns of interaction. For some couples, this work leads to a stronger, more secure relationship. The process of addressing these issues can create deeper understanding and more authentic connection. However, others may discover that the healthiest path forward is separation, particularly if one partner is unwilling to engage in the necessary therapeutic work. Effective therapeutic intervention for accusatory relationship patterns requires a carefully structured approach combining multiple evidence-based techniques. Here's an examination of specific interventions that have shown promise in addressing these complex dynamics. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) serves as a foundational approach, particularly for the accusing partner. The therapist helps identify triggering situations and the automatic thoughts that follow – for instance, "My partner is working late again, they must be cheating." Through thought recording exercises, the accuser learns to recognize these cognitive distortions and develop more balanced interpretations. They might reframe the thought to, "Working late is a normal part of their job, and they've always been transparent about their schedule." Attachment-Based Therapy focuses on healing early wounds that fuel the accusatory behavior. This approach often employs the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI) to understand the accuser's attachment style and its origins. Therapeutic techniques might include inner child work, where the accuser dialogues with their younger self to address unmet needs and fears of abandonment. This process helps separate past trauma responses from present relationship dynamics. For the accused partner, Trauma-Focused Therapy often proves beneficial, as living under constant suspicion can create its own form of trauma. Techniques like EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) help process the emotional impact of chronic accusations and restore a sense of personal agency. Boundary-setting exercises and assertiveness training help rebuild their eroded sense of self. In couples work, the Gottman Method offers specific tools for rebuilding trust and communication. The "Stress-Reducing Conversation" technique creates a daily ritual where partners discuss their stresses without problem-solving, fostering empathy and connection. "State of the Union" meetings provide a structured format for addressing concerns without triggering defensive reactions. Mindfulness-based interventions help both partners develop awareness of their emotional triggers and physiological responses. The accuser learns to recognize the bodily sensations that precede accusatory thoughts, while the accused partner identifies signs of emotional overwhelm. Simple techniques like the "STOP" method (Stop, Take a breath, Observe, Proceed mindfully) help interrupt escalating cycles. Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP) techniques, adapted from anxiety treatment, can help the accusing partner tolerate uncertainty. Graduated exposure to trigger situations – like their partner attending social events alone – paired with prevention of checking behaviors, helps build distress tolerance. This work requires careful calibration and strong therapeutic support to avoid overwhelming either partner. Role-playing exercises in therapy allow couples to practice new communication patterns in a safe environment. The therapist might guide them through "accusation scenarios," teaching the accuser to express fears without making accusations, while the accused partner learns to respond with empathy while maintaining healthy boundaries. These exercises often incorporate "time-out" protocols for when emotions become too intense. Written exercises play a crucial role in the healing process. Therapeutic journaling helps both partners process their experiences outside of sessions. The accuser might maintain a "reality-testing log" documenting the gap between their fears and actual events, while the accused partner uses writing to reconnect with their authentic self and process suppressed emotions. Long-term maintenance of healthy relationship patterns requires vigilant attention to potential relapse triggers and the implementation of robust prevention strategies. This phase of recovery focuses on solidifying therapeutic gains while preparing couples for future challenges. The foundation of successful maintenance lies in what therapists call the "Early Warning System." Both partners learn to identify subtle signs that old patterns are re-emerging. For the accusing partner, these might include increased checking behaviors, intrusive thoughts about infidelity, or physical symptoms of anxiety. The accused partner might notice themselves beginning to self-censor or experiencing renewed hypervigilance about their actions. Successful couples develop personalized "Relationship Maintenance Plans" that outline specific strategies for different risk levels. These plans typically include: Level 1 (Daily Maintenance): Regular check-ins using structured communication techniques Consistent practice of mindfulness exercises Maintaining separate interests and healthy boundaries Ongoing journaling to track emotional patterns Regular engagement in shared positive activities Level 2 (Yellow Flags): Implementation of time-out protocols when tensions rise Increased use of cognitive restructuring techniques Return to basic grounding exercises Activation of support networks Review of therapy notes and coping strategies Level 3 (Red Flags): Immediate contact with their therapist Return to more intensive therapeutic support Implementation of crisis communication protocols Temporary return to structured interaction guidelines Increased frequency of support group attendance A crucial aspect of maintenance involves "Stress Inoculation Training," where couples deliberately expose themselves to mild triggering situations under controlled conditions. This might include practicing healthy responses to common triggers like work-related travel, social media interactions, or delayed text responses. These exercises help build resilience and confidence in their new coping mechanisms. The concept of "Relationship Resilience" becomes central during this phase. Couples learn that occasional setbacks don't indicate failure but rather provide opportunities for reinforcing their recovery skills. They develop what therapists term "emotional muscle memory" – the ability to automatically implement healthy responses to challenging situations. Support systems play a vital role in maintenance. Successful couples often participate in ongoing support groups or maintenance therapy sessions, viewing these as relationship wellness check-ups rather than crisis interventions. Some find that serving as mentors to other couples working through similar issues helps reinforce their own recovery. Technology can be repurposed from a source of conflict to a maintenance tool. Couples might use relationship apps that promote healthy communication or set up regular virtual check-ins with their therapist. However, clear boundaries around technology use remain essential to prevent slipping back into monitoring behaviors. Perhaps most importantly, couples learn to celebrate their progress while remaining realistic about ongoing challenges. They understand that maintaining relationship health requires active engagement, much like physical fitness requires regular exercise. This mindset shift from "fixing a problem" to "maintaining relationship wellness" proves crucial for long-term success. Long-term studies of couples who have navigated through accusatory relationship patterns reveal diverse outcomes that can inform both therapeutic approaches and prognosis. Understanding these trajectories helps set realistic expectations and guides intervention strategies. Research indicates three primary long-term outcome patterns. The first group, approximately 30% of couples, achieves what therapists term "transformed intimacy" – a deeper, more authentic connection built on the foundation of their recovery work. These couples often report that working through their trust issues created unprecedented emotional intimacy and self-awareness. Their relationships become characterized by earned security rather than anxious attachment. The second group, roughly 45%, maintains stability through ongoing management. These couples successfully implement their maintenance strategies but require periodic therapeutic tune-ups. Their relationships remain functional and satisfying, though they may experience occasional resurgences of old patterns during high-stress periods. The key distinction is their ability to recognize and address these patterns before they escalate. The final group, about 25%, ultimately transitions to new relationships or chosen singlehood. Importantly, research suggests that even these "unsuccessful" couples often report personal growth and improved relationship skills in their subsequent relationships, particularly when both partners engaged meaningfully in the therapeutic process. Looking beyond the immediate relationship, the implications of successful recovery extend into multiple life domains. Professional performance often improves as mental energy previously consumed by relationship anxiety becomes available for career focus. Social relationships deepen as both partners develop healthier boundaries and interaction patterns. Many couples report improved parenting capacity, breaking intergenerational patterns of insecure attachment. The neurobiological impact of successful treatment appears lasting. Brain imaging studies of recovered accusers show normalized activity in areas associated with threat detection and emotional regulation. This suggests that with proper intervention, even deeply ingrained patterns of hypervigilance can be permanently altered. Perhaps most significantly, couples who successfully navigate this journey often become valuable resources for others facing similar challenges. Many choose to participate in peer support programs or share their experiences in therapeutic groups, creating a ripple effect of healing in their communities. Their stories serve as powerful testimonials that change is possible, even in seemingly entrenched patterns of mistrust. The future of treatment for accusatory relationships continues to evolve, with promising developments in areas like neurofeedback therapy and virtual reality exposure training. However, the fundamental principles remain consistent: healing requires courage, commitment, and the willingness to confront deep-seated patterns while building new ones. As we understand more about the intersection of attachment theory, neurobiology, and relationship dynamics, one truth becomes increasingly clear: while the path to recovery from accusatory patterns is challenging, it offers an opportunity for profound personal and relational transformation. The journey itself, regardless of its ultimate destination, can serve as a catalyst for meaningful growth and self-discovery.

Chapter 1: The Performance Sarah Mitchell considered herself one of the good ones. At thirty-two, she'd attended every diversity workshop her tech company offered, had a "Black Lives Matter" sticker on her laptop, and wasn't afraid to call out racism wherever she saw it — which, as it happened, was everywhere. The problem was, Sarah saw racism in places where it didn't exist. Like when her colleague James suggested that maybe — just maybe — the office's mandatory "Unconscious Bias" training wasn't the best use of company time. Sarah immediately reported him to HR for creating a hostile work environment. Or when her neighbor Tom put up a "Blue Lives Matter" flag. She didn't just write a strongly-worded letter to the HOA; she started a neighborhood petition to have him removed from the community. The fact that Tom's son was a police officer who'd died in the line of duty was, in Sarah's mind, irrelevant. Symbols were symbols, after all. But Sarah's moment of reckoning came during the company's annual diversity gala. As she stood at the podium, ready to accept an award for her "outstanding contributions to workplace inclusion," an elderly Black janitor shuffled past with his mop. Sarah, caught up in her performative zeal, stopped her speech to publicly praise him for his "brave presence in predominantly white spaces." The janitor, Mr. Johnson, who held two master's degrees and worked nights to put his grandchildren through college, simply stared at her. The silence in the room was deafening. It was then that Sarah began to realize that perhaps she, in her desperate attempt to prove her anti-racist credentials, had become something else entirely: a caricature of white liberal guilt, so focused on appearing virtuous that she'd lost sight of actual human beings. But would she recognize this truth about herself? Or would she double down, convinced that her crusade against perceived racism made her one of the "good ones"? After all, nothing was more important to Sarah than being seen as one of the good ones. Even if it meant destroying other people's lives in the process. Sarah's phone buzzed. Another notification from her carefully curated social justice Twitter feed. Someone had posted about a local Thai restaurant owned by a white couple. Her fingers itched with righteous purpose as she began drafting her callout post. "Time to educate some colonizers," she muttered, completely missing the irony of her white savior complex in action. She had a fresh thread brewing about cultural appropriation in the culinary arts, complete with her usual hashtags: #CulturalViolence #NotYourFood #CancelColonizers. The fact that she'd never actually eaten at the restaurant, or spoken to its owners, or learned anything about their background, was irrelevant. She had a cause to fight for, and more importantly, an audience to perform for. Her laptop screen reflected her satisfied smile as she hit "Tweet." Another blow struck in the name of justice. Another performance completed. In the building's lobby, Mr. Johnson quietly mopped the floor, his MIT class ring catching the fluorescent light as he moved. He'd watched people like Sarah come and go over his decades of working nights to fund his grandchildren's education. They never asked about his dissertation on economic empowerment in urban communities, or his years running a successful consulting firm before the 2008 crash. They just saw what they wanted to see: a prop in their performance of virtue. Mr. Johnson smiled slightly, knowing something Sarah didn't: real change happened in the quiet moments between the performances, in the authentic connections made when nobody was watching, in the humble act of seeing people as they were – not as characters in your own story of redemption. But Sarah wasn't ready for that lesson yet. She was too busy composing her next thread about why white people shouldn't be allowed to use chopsticks. The spotlight was on, and she had a show to run. Chapter 2: The Awakening Sarah's Instagram feed was her battlefield. Every morning, she'd scroll through her carefully curated list of "anti-racist educators," taking detailed notes on the latest terminology and transgressions to avoid. Her followers had come to expect her daily callouts of problematic behavior, accompanied by lengthy captions explaining why seemingly innocent actions were actually "deeply rooted in white supremacy." Today's target was the local farmer's market. "Just witnessed a white vendor selling KIMCHI," she typed furiously. "This is literally colonization on a plate. I immediately spoke to the manager about this gross example of cultural appropriation." What Sarah hadn't bothered to learn was that the vendor, Amy Chen, was Korean-American, using her grandmother's recipe. Amy had been wearing a sun hat and face mask while tending her stall, making her ethnicity not immediately apparent. But Sarah hadn't asked. Asking would have ruined a perfectly good opportunity for outrage. The backlash was swift. Amy's regular customers came to her defense, and soon Sarah's inbox was flooded with messages explaining her mistake. But Sarah wasn't interested in correction. Instead, she doubled down, writing a three-part series about how her critics were exhibiting "white fragility" and "defending systems of oppression." That evening, during her weekly video call with her sister Kate, Sarah proudly recounted her day of activism. "Don't you think you should apologize to the vendor?" Kate asked carefully. "God, Kate, you sound just like Mom," Sarah snapped. "This is exactly why I had to distance myself from our family. You're all so... problematic." Kate sighed. Their mother — a retired civil rights lawyer who'd spent forty years defending low-income clients of all backgrounds — had become Sarah's favorite example of "outdated thinking" ever since she'd suggested that perhaps screaming "racist" at their elderly neighbor for mispronouncing a name wasn't the most constructive approach. "Sarah," Kate said, "do you remember Ms. Washington from third grade?" "Our Black teacher? Of course. She was so brave to work in our predominantly white school." "She wasn't brave, Sarah. She was just a teacher doing her job. And she hated being called 'brave' for simply existing in white spaces. She told us that directly, remember?" Sarah didn't remember. Or rather, she'd rewritten that memory to better fit her current narrative. The conversation ended abruptly when Sarah spotted a Facebook post she deemed problematic — a white woman sharing a recipe for tacos. "Sorry, Kate, duty calls. This cultural theft needs to be addressed." As she began typing another righteously indignant post, Sarah caught her reflection in the computer screen. For a brief moment, she saw something in her eyes that made her pause: a glimpse of emptiness, a hunger for validation that no amount of virtual signaling could fill. But then the moment passed, and she returned to her crusade. After all, someone had to protect the world from the scourge of white people making tacos. Meanwhile, across town, Amy Chen added another name to her growing list of banned customers, turned up her K-pop playlist, and continued fermenting her grandmother's kimchi — the same way her family had done for generations, regardless of who approved or disapproved of their right to do so. Chapter 3: The Committee Sarah's greatest triumph — or so she thought — was founding her company's "Coalition for Radical Inclusion and Social Justice" (CRISJ, which she insisted on pronouncing as "crisis"). Every Tuesday, the committee would meet in Conference Room B to discuss ways to make their workplace more equitable. Today's meeting was particularly energetic. Sarah had discovered that the company's cafeteria was serving "ethnic food Fridays." "It's exotification of minority cuisines," she declared to the room of predominantly white faces she'd personally selected for the committee. "And the worst part? They're letting Chef Marcus, who is literally a white male, cook these dishes!" Maria, one of only two people of color on the committee, cleared her throat. "Actually, Marcus trained in Thailand for ten years, and his wife is Thai—" "That's literally worse," Sarah interrupted, making a note to schedule a private conversation with Maria about her "internalized oppression." "He's basically colonizing his wife's culture for profit." The committee members nodded dutifully, except for James from Accounting, who'd only joined because HR strongly suggested it would help with his "documented insensitivity" — namely, the time he'd questioned Sarah's anonymous complaint about the office Christmas party being "religious terrorism." "What if we just asked the staff what they think about the menu?" James suggested. Sarah's eyes narrowed. "That would be putting the burden of education on marginalized people, James. Do better." She made another note to report this microaggression to HR. After the meeting, Sarah headed to her favorite coffee shop, The Woke Bean, where she regularly lectured the baristas about their tip jar being a symbol of capitalism's exploitation. As she waited for her order ("fair trade, ethically sourced, oat milk cortado with a trigger warning"), she overheard two elderly Asian women chatting at a nearby table. "Did you hear they're canceling ethnic food at TechCorp?" one said. "My daughter Jin works there. She said some white lady decided it was offensive." "Typical," her friend replied. "They think they're helping, but they're just erasing us. Jin said that Marcus's pad thai was the only thing that reminded her of her grandmother's cooking." Sarah felt a strange discomfort in her stomach. But she quickly diagnosed it as a reaction to systemic oppression rather than any sort of self-doubt. Opening her laptop, she began drafting an email to the entire company about the importance of "decolonizing lunch." That's when she noticed a new employee standing by her table — Dr. Yuki Chen, the company's recently hired VP of Innovation. Sarah immediately straightened up, ready to demonstrate her allyship. "Dr. Chen! I just want you to know that I see you, and I honor your brave journey as an Asian woman in tech. I'm actually leading the charge to remove the problematic ethnic food program that's been oppressing our marginalized employees." Dr. Chen's expression was unreadable behind her mask, but her voice was crystal clear: "Ms. Mitchell, I'm the one who started the ethnic food program. And Marcus is my brother-in-law." For the first time in years, Sarah was speechless. "Also," Dr. Chen continued, "I've been meaning to talk to you about some complaints I've received about CRISJ. Would you mind joining me in my office tomorrow morning?" As Dr. Chen walked away, Sarah frantically opened Slack to message her committee. They needed to organize a protest immediately. Clearly, Dr. Chen was suffering from internalized white supremacy, and it was Sarah's duty — her burden, really — to save her from herself. After all, what could an actual Asian executive possibly know about diversity that Sarah hadn't already learned from her Instagram activism course? Chapter 4: The Reckoning Sarah arrived at Dr. Chen's office armed with screenshots of anti-racist infographics and a 47-page document titled "Decolonizing Corporate Cuisine: A White Ally's Guide to Food Justice." She'd stayed up until 3 AM preparing her defense, fueled by organic coffee and the conviction that she was on the right side of history. Dr. Chen's office was disappointingly conventional. Sarah had expected at least a few "Asian-inspired" decorative elements she could mentally catalog as problematic. Instead, she found herself sitting across from a simple desk with a family photo — Marcus, the cafeteria chef, was indeed in the picture, arm around his wife at what appeared to be Dr. Chen's graduation. "Ms. Mitchell," Dr. Chen began, adjusting her glasses, "I've reviewed the activities of your... committee." She glanced at a folder. "CRISJ?" "Yes," Sarah leaned forward eagerly. "We're working to dismantle systemic—" "In the past month," Dr. Chen continued as if Sarah hadn't spoken, "you've filed thirty-seven HR complaints, organized a boycott of the company gym for offering 'culturally appropriative' yoga classes, and demanded the removal of the Spanish language option from our software because, according to your email, 'white developers shouldn't profit from other languages.'" "Exactly!" Sarah beamed. "I'm so glad you understand—" "Our yoga instructor is Hindu, Ms. Mitchell. She's been teaching for twenty years. She quit last week after your followers left one-star reviews on her personal business page." "Well, she should have understood that as a white-passing person—" "She's not 'white-passing.' That's just what she looks like. And she's filed a harassment claim." Sarah felt a familiar rush of righteous indignation. "This is exactly the kind of tone policing that—" "I'm not finished," Dr. Chen's voice had a steel edge to it. "The Spanish language option was developed by our Latin American team in Mexico City. They were quite confused by your email accusing them of 'letting themselves be colonized.'" Sarah's phone buzzed. Probably another Instagram notification from her latest post about "decentering whiteness in corporate spaces." Dr. Chen reached over and turned the phone face-down. "But let's talk about Marcus." "The colonizer chef?" Sarah regretted the words as soon as they left her mouth. "My brother-in-law. The one you reported to the health department for 'cultural food crimes.'" Dr. Chen's voice remained steady. "The one who learned to cook in my mother's restaurant after his parents died. The one who helped put me through graduate school by working double shifts. That colonizer." For the first time, Sarah noticed other photos on Dr. Chen's desk. A younger Marcus in a Thai kitchen, covered in flour. Marcus at a hospital, holding a newborn. Marcus and his wife teaching a cooking class. "I... I was just trying to help," Sarah's voice sounded small, even to herself. "Were you?" Dr. Chen opened her laptop. "Because I have an interesting email here from 2019. Before your... awakening. You wrote to HR complaining about, and I quote, 'the overwhelming food smells' when Marcus first introduced Asian dishes to the cafeteria menu." Sarah felt the blood drain from her face. She'd forgotten about that email. "Your activism, Ms. Mitchell, seems to have coincided perfectly with the rise of social media virtue signaling. Before that, you were filing very different kinds of complaints." Dr. Chen slid a document across the desk. Sarah recognized the company letterhead. "This is a final warning," Dr. Chen said quietly. "Your behavior has created a hostile work environment — not for the people you claim to protect, but through your persistent harassment of employees who don't conform to your view of what their cultures should be." "But I'm an ally!" Sarah's voice cracked. "No, Ms. Mitchell. You're a bully with a hashtag." As Sarah left the office, her carefully constructed world of performative activism beginning to crack, she passed the cafeteria. Through the window, she saw Marcus teaching a group of employees how to fold dumplings, everyone laughing as their attempts fell apart. She remembered writing an email draft about the "problematic power dynamics" of that cooking class. For the first time, she wondered if perhaps she'd been the problem all along. Her phone buzzed again. Another notification. Another chance to be publicly righteous. Her finger hovered over the screen. But this time, something stopped her. Chapter 5: The Unraveling Sarah spent the weekend in crisis. Not the usual kind where she'd discover a white-owned sushi restaurant and organize a Twitter mob, but a real one. Her carefully curated world of performative outrage was crumbling, and worse — people were starting to notice. Her phone kept buzzing with notifications from her latest crusade, but each one now felt like an accusation. She scrolled through her post history with growing horror: "This white woman wearing hoop earrings at the grocery store is LITERALLY committing violence..." "Just watched my neighbor eating with chopsticks. As a white ally, I had to say something..." "Thread: Why having a world foods aisle in supermarkets perpetuates colonial supremacy (1/47)..." It was while hate-following her neighbor Tom's Facebook page (looking for problematic content to report) that she saw it: a photo of him at his son's grave, the "Blue Lives Matter" flag gently waving in the background. The caption read: "Five years without you, son. Miss you every day." Sarah felt physically ill. She remembered the change.org petition she'd started to have him evicted, the anonymous letters she'd sent to his employer, the Instagram stories she'd posted about the "racist cop supporter" next door. She clicked through to his profile, something she'd never bothered to do before. There were photos of his son's community service work, his volunteer activities at the local youth center, his graduation from the police academy with a stated mission to improve police-community relations. The last photo showed him mediating a peaceful discussion between protesters and police officers, one week before a drunk driver took his life. "Oh god," Sarah whispered to her empty apartment. Her phone buzzed again. The CRISJ group chat was on fire. In her absence, they'd discovered that the company's janitorial service was owned by a Hispanic family. "Cultural exploitation!" someone posted. "They're forcing minorities into servitude roles!" "Actually," replied another member, "the owner has an MBA and built the company from scratch. They pay above market rate and provide full benefits." "STOP DEFENDING THE OPPRESSORS!" Sarah recognized her own rhetorical style in their responses, and it made her cringe. Was this how she sounded? She thought about Mr. Johnson from the diversity gala, how she'd never bothered to learn about his degrees or his grandchildren. She'd been too busy using him as a prop in her performance of virtue. Her doorbell rang. Through the peephole, she saw Tom, the neighbor she'd spent months trying to destroy. He was holding a plate of cookies. "Your sister Kate told me you might be having a rough time," he said when she hesitantly opened the door. "Thought you might like some of these. They're my son's recipe. He used to make them for the kids at the youth center." Sarah stood frozen, the plate warm in her hands. "I know what you've been doing, Sarah," he continued, his voice tired but not unkind. "The letters to my boss, the petition, the posts about me. I want you to know I forgive you. And if you ever want to actually talk — about my son, about what he believed in, about anything — I'm right next door." As Tom walked away, Sarah noticed a group of her CRISJ committee members across the street, phones raised, documenting what they probably saw as her "fraternization with the enemy." She should have cared about their judgment. A week ago, she would have cared about nothing else. Instead, she closed her front door, set down the plate of cookies, and for the first time in years, opened her laptop not to condemn, but to learn. She typed into Google: "How to apologize and make amends." Her phone buzzed one more time. It was an email from Dr. Chen: "When you're ready to do the real work — not the performative kind — come see me. Bring an appetite. Marcus is teaching another cooking class, and this time, you're actually invited to listen and learn." Sarah looked at the cookies Tom had brought, picked one up, and took a bite. It was sweet, complex, and nothing like she'd expected. Kind of like people, she thought, when you actually took the time to know them. Chapter 6: The Real Work Sarah deleted her social media accounts on a Tuesday. There was no dramatic announcement, no lengthy explanation about "taking space for self-reflection" — phrases she now recognized as part of her previous performance. She simply clicked "delete account" five times and felt the weight of constant outrage lift from her shoulders. The CRISJ committee imploded within days of her departure. Without their leader, they'd devolved into accusing each other of increasingly absurd transgressions. The last straw came when someone reported the office's artificial plants as "appropriating nature-based indigenous traditions." But Sarah wasn't there to see it. She was in the company cafeteria, sweating over a hot stove with Marcus. "No, no," he laughed, adjusting her grip on the wok. "You're treating it like it's going to bite you. Feel the weight, move with it." He demonstrated the fluid motion of proper stir-frying. "My mother-in-law taught me this. Took me three years to get it right." "Three years?" Sarah was shocked. "But I thought—" "That I just decided to 'colonize' Asian cuisine one day?" His eyes twinkled. "That's the problem with assumptions, Sarah. They make for quick judgments but slow learning." Dr. Chen appeared with a stack of bowls. "Ah, I see you haven't set anything on fire yet. Progress." Sarah blushed, remembering her previous manifesto about how letting white people cook Asian food was "culinary colonialism." Now she understood the staggering arrogance of having written that without ever having tried to make the food herself, without knowing the stories behind each dish, without understanding that cuisine, like culture, was meant to be shared and celebrated, not policed and segregated. "I have something for you," Dr. Chen said, pulling out a worn notebook. "My grandmother's recipes. The real ones, not the simplified versions we serve here. But first, you need to learn the history." And so Sarah learned. Not by posting about it on Instagram, but by listening. Really listening. She learned how Dr. Chen's grandmother had modified her recipes during the Cultural Revolution, when traditional ingredients were scarce. How Marcus had learned to cook as therapy after losing his parents, finding family in the warm chaos of a restaurant kitchen. How food had been their language of love when words failed across cultural and linguistic barriers. After the lesson, Sarah walked home, her arms sore from wok-handling and her notebook filled with actual knowledge instead of performative outrage. She passed Tom's house and saw him in the garden. "Hey," she said, stopping at his fence. "I've been meaning to ask... would you tell me about your son?" Tom's face softened. "Come on in. I'll make coffee." For the next two hours, Sarah did something she hadn't done in years: she shut up and listened. Tom showed her photos, told her stories about his son's dedication to community policing, his dreams of reform from within the system, his belief that real change came from understanding, not shouting. "He used to say," Tom recalled, his voice thick with emotion, "that the hardest part of his job wasn't dealing with criminals. It was dealing with people who were so convinced they were right that they couldn't hear anyone else." Sarah felt the words like a punch to the gut. That night, she began writing emails. Not manifestos or callouts, but apologies. To the yoga instructor. To the Spanish development team. To Mr. Johnson. To everyone she'd tried to "save" without bothering to know. Some responded with forgiveness. Others didn't respond at all. Sarah learned to sit with that discomfort, understanding that real growth wasn't about being seen as good — it was about doing better, even when no one was watching. Her phone lay silent, notifications turned off. On her kitchen counter, a wok seasoned with actual experience replaced her collection of "Decolonize Everything" coffee mugs. And on her laptop, instead of another angry blog post, she was writing something new: "Dear Dr. Chen, I'm ready for the next lesson. Not just about cooking, but about listening. About learning. About doing the real work. And yes, I know now that the real work doesn't come with a hashtag. • Sarah" Chapter 7: Full Circle One year later, Sarah sat in Conference Room B, the same room where she'd once held court with CRISJ. But today was different. Across from her sat a young white woman named Rebecca, clutching a stack of printed tweets and vibrating with familiar righteous energy. "These microaggressions cannot stand," Rebecca declared, spreading screenshots across the table. "The cafeteria is literally serving General Tso's chicken. It's not even authentic! As a white ally, I have to speak up for—" "Have you tried it?" Sarah interrupted quietly. Rebecca blinked. "What?" "The chicken. Have you tried Marcus's version?" "Well, no, but that's not the point. The point is—" "Come with me," Sarah said, standing up. She led a confused Rebecca to the cafeteria, where Marcus was teaching a group of employees how to properly bread the chicken pieces. "General Tso's chicken," Marcus explained to the group, "was actually invented in New York City by Chef Peng Chang-kuei. He created it for American palates while maintaining Chinese cooking techniques. Our version here uses his original recipe, which he shared with my wife's family when they ran a restaurant together in Taiwan." Rebecca deflated slightly. "But... but I read a thread on Twitter..." "I know," Sarah said softly. "I used to write those threads." After Marcus's class, Sarah bought Rebecca lunch. Over plates of perfectly crispy General Tso's chicken, Sarah shared her own journey from performative outrage to genuine understanding. "But how do we fight racism if we can't call it out?" Rebecca asked, her worldview visibly shaking. "By doing the actual work," Sarah explained. "Remember Mr. Johnson, the janitor I tried to 'save' at the diversity gala? He now teaches night classes in business administration here at the company. I take his class. Not to prove anything to anyone, but because he has thirty years of experience I can learn from." She told Rebecca about the community program she'd started with Tom, bringing local police officers and neighborhood kids together for cooking classes taught by Marcus. No social media posts, no public accolades — just quiet, meaningful work. "But nobody knows about all the good you're doing," Rebecca protested. "Exactly," Sarah smiled. "That's how I know it's real." As if on cue, Dr. Chen appeared at their table. "Sarah, we need your help," she said. "The city council is considering a proposal to ban 'non-traditional' businesses from the historic district. Some of our restaurant owners are worried." The old Sarah would have immediately drafted a Twitter thread about systemic oppression. The new Sarah asked, "When's the council meeting? I'll bring the small business impact studies we've been working on, and maybe Marcus can cater it—show them what 'traditional' really means in our community." Rebecca watched this exchange with growing understanding. "Could... could I help too?" Sarah and Dr. Chen exchanged glances. "Of course," Dr. Chen said. "But first, you'll need to learn the difference between helping and performative helping. Sarah's pretty good at explaining that nowadays." That evening, Sarah walked home past Tom's house. The Blue Lives Matter flag was gone, replaced by a garden of flowers his son had always wanted to plant. They were tended jointly by Tom and local teenagers from Sarah's community program. Her phone buzzed—her first social media notification in a year. Someone had tagged her in a callout post: "Remember Sarah Mitchell? The so-called ally who betrayed the cause by actually talking to the enemy?" Sarah laughed and deleted the notification. In her kitchen, a pot of soup simmered—her first solo attempt at Dr. Chen's grandmother's recipe. It wasn't perfect, but it was authentic. Like her allyship now: messy, imperfect, but real. She ladled out two bowls and headed next door. Tom would want to hear about today's council meeting prep, and she wanted his perspective on community outreach. Not for show, not for social media, not to prove she was "one of the good ones." But because that's what neighbors do. That's what people do, when they stop performing and start living. The End Epilogue: The Ripple Effect Three years after Sarah's "cancellation" from social justice Twitter, her old CRISJ committee photo popped up in her Facebook memories. She barely recognized herself in that image: standing at the front, finger pointed mid-lecture, surrounded by a sea of nodding white faces competing to look the most concerned. Today, she sat in a very different kind of meeting. The community center's conference room was chaos – Marcus demonstrating dumpling-folding techniques to a group of police cadets, Tom's gardening club teenagers teaching elderly residents about sustainable farming, and Mr. Johnson conducting a small business workshop in the corner. Dr. Chen stood beside Sarah, both of them watching Rebecca – yes, that Rebecca – patiently explaining social media marketing to immigrant business owners fighting the historic district restrictions. "Remember when you thought activism meant having the loudest megaphone?" Dr. Chen asked, sampling one of the dumplings. Sarah winced. "Please don't remind me." "No, actually, I think we should remind you." Dr. Chen pulled out her phone and showed Sarah a text message. It was from the yoga instructor Sarah had once tried to cancel: "Starting free classes at the community center next week. Tell Sarah she was right about one thing – yoga should be accessible to everyone. Just not for the reasons she thought." The door chimed as Tom's neighbor Maria walked in with her teenage son Miguel. Three years ago, Sarah would have immediately labeled Maria a "problematic Latina" for supporting Tom. Now, she knew Maria as the brilliant civil rights attorney who'd helped save three immigrant-owned restaurants from the historic district ban, and Miguel as the talented chef apprenticing under Marcus. "Hey, Sarah," Miguel called out, "I modified your soup recipe with some of my abuela's spices. Want to try?" Sarah laughed. "You mean the recipe I nearly got Marcus fired for sharing? Please tell me you made it better." "Speaking of better," Dr. Chen said, "Have you seen this?" She handed Sarah a printout of a Twitter thread. Sarah's stomach clenched – she still had a Pavlovian response to Twitter's format – but this was different. Someone had written a thoughtful analysis of how their community had transformed over the past three years. No accusations, no callouts, just reduced police incidents, increased small business ownership, improved community relations. "The best part?" Dr. Chen smiled. "Nobody knows you had anything to do with it. No hashtags, no viral moments, no performance." "Thank god," Sarah muttered. The door chimed again. A young white woman walked in, clutching her phone and practically vibrating with familiar righteous energy. Sarah recognized the look – she'd worn it herself not so long ago. "Is this where the anti-racism workshop is being held?" the woman demanded. "I have some concerns about cultural appropriation in this neighborhood. I've drafted a thread—" "Perfect timing," Sarah interrupted, exchanging knowing looks with Dr. Chen. "Marcus is just about to teach us how to make dumplings. Would you like to learn the story behind them?" "I don't need to learn about—" "Yes, actually, you do," Sarah said gently. "We all do. Here, wash your hands. The first lesson isn't about dumplings at all – it's about listening." As she guided the newcomer toward the cooking station, Sarah caught her reflection in the window. Her face was smudged with flour, her "activist" wardrobe replaced with practical cooking clothes, and she was smiling – really smiling, not the performative kind she used to perfect for Instagram. Her phone buzzed. Another callout post about her "betrayal of the cause" was making the rounds. Sarah ignored it and rolled up her sleeves. There were dumplings to be made, stories to be shared, and actual work to be done. Later that night, as the community center emptied, Sarah found a note tucked under her coat. In Mr. Johnson's elegant handwriting, it read: "Real change doesn't need an audience. - Your favorite 'brave presence in white spaces' 😉" Sarah pinned the note to the community center's board, right next to the sign-up sheet for next week's cooking classes. The sheet was already full of names – police officers and protesters, immigrants and old-timers, social justice warriors and skeptics, all signed up to learn, to listen, to do the real work. No hashtags required. Fin Author's Note: Behind "The Virtue Signal" When I set out to write "The Virtue Signal," I aimed to explore one of the most complex and delicate issues in modern discourse: the phenomenon of performative activism and false accusations of racism among white people. The story needed to walk a careful line - examining these behaviors critically while avoiding the very same pitfalls of self-righteousness it sought to critique. Sarah's character was inspired by what sociologists have termed "white savior complex" - the tendency for some white individuals to view themselves as the rescuers or protectors of people of color, often while inadvertently perpetuating harmful stereotypes and power dynamics. Her journey from performative outrage to genuine understanding mirrors a path many well-meaning people must navigate in our social media age. The supporting characters were deliberately crafted to subvert the shallow stereotypes that performative activists often deploy. Mr. Johnson isn't just a janitor but a business expert with multiple degrees. Marcus isn't a cultural appropriator but someone who earned his expertise through years of dedicated study and family connection. Dr. Chen isn't a passive victim of colonization but a powerful executive who understands the complexity of cultural exchange. The choice to make Sarah's victims primarily other white people was intentional - it highlights how performative activism often says more about the accuser's need for validation than any genuine concern for social justice. Tom's story, in particular, shows how quick judgments based on symbols (like the Blue Lives Matter flag) can blind us to human complexity and pain. The story's structure follows Sarah's transformation from performing goodness to doing good: • Chapters 1-3 show her at the height of her performative phase • Chapters 4-5 mark her crisis and beginning of awareness • Chapters 6-7 demonstrate her growth into genuine allyship • The Epilogue shows the real-world impact of choosing authentic action over performance Some readers might notice that the story doesn't offer easy answers or complete redemption. Sarah's former targets don't all forgive her. Her new approach isn't perfect or pure. This messiness is intentional - real growth and genuine allyship aren't about achieving a perfect end state, but about committing to a continuous journey of learning and understanding. The recurring motif of food throughout the story serves multiple purposes. It represents cultural exchange at its most fundamental level, challenges simplistic notions of authenticity and appropriation, and provides a tangible way to show how learning about other cultures requires humility, patience, and a willingness to make mistakes. Perhaps most importantly, the story suggests that real social justice work often happens quietly, without social media attention or public accolades. It's in the daily actions, the difficult conversations, the humble learning moments that true change occurs. As Sarah learns, it's not about being seen as "one of the good ones" - it's about doing the actual work, especially when no one is watching. The ending brings a new performative activist into the community center, suggesting that this cycle continues - but also that there's hope for transformation, if we're willing to put down our phones, roll up our sleeves, and do the real work of building understanding. In our current climate of social media activism and call-out culture, I hope this story encourages readers to examine their own motivations and actions. Are we performing goodness, or doing good? Are we listening to understand, or waiting to speak? Are we building bridges, or burning them for likes and retweets? These are questions without easy answers, but they're questions worth asking. Because in the end, real change doesn't come from hashtags or viral posts - it comes from the messy, complex, often invisible work of genuine human connection. • Hyper December 2024 Reading Guide: "The Virtue Signal" Discussion Questions & Analysis Character Analysis 1. Sarah's Evolution o How does Sarah's language change throughout the story? Track specific phrases and terms she uses from beginning to end. o At what moment does Sarah first show genuine self-awareness? Are there earlier hints that she might be capable of change? o Is Sarah a sympathetic character? Does your sympathy for her change throughout the story? 2. Supporting Characters o Why is Dr. Chen portrayed as calm and measured rather than angry at Sarah's behavior? What purpose does this serve in the narrative? o How does Tom's character challenge Sarah's (and perhaps readers') preconceptions about people who display certain political symbols? o What role does Marcus play beyond just being a chef? How does his character challenge stereotypes about cultural authenticity? Themes & Symbols 1. Food as Metaphor o How does the story use cooking and food sharing as a metaphor for cultural exchange? o What does the contrast between Sarah's initial reaction to "ethnic food" and her later cooking lessons represent? o Why is learning to cook portrayed as more meaningful than learning to speak about cultural issues? 2. Social Media & Performance o How does the story portray the relationship between social media activism and real-world change? o What does Sarah lose when she gives up her social media presence? What does she gain? o How does the story distinguish between performative and genuine allyship? 3. Power & Privilege o How does Sarah's initial behavior actually reinforce the power dynamics she claims to fight against? o What does the story suggest about the relationship between intention and impact in activism? o How does Sarah's privilege manifest differently before and after her transformation? Critical Questions 1. On Activism o Is the story suggesting that all social media activism is inherently performative? Where is the line? o How does the story define "real work" in terms of social justice? Do you agree with this definition? o What does the story suggest about the role of public versus private actions in creating social change? 2. On Growth & Change o Is Sarah's transformation believable? What makes it so (or not)? o Why do some characters forgive Sarah while others don't? Is this realistic? o What role does humility play in Sarah's journey? How is this shown in the text? 3. On Community o How does the community center in the epilogue differ from Sarah's original CRISJ committee? o What does the story suggest about the relationship between authentic community building and social justice? o Why does the story end with the appearance of a new "Sarah"? What does this cyclical element suggest? Contemporary Relevance 1. Current Events & Context o How does this story relate to contemporary discussions about "wokeness" and "cancel culture"? o What does the story suggest about the role of white people in anti-racist work? o How might different readers interpret this story based on their own experiences with activism? 2. Personal Application o Have you witnessed instances of performative activism in your own life? How did they compare to Sarah's behavior? o What does this story suggest about how to handle our own mistakes and growth in social justice work? o How might this story change the way readers approach social media activism? Writing Craft 1. Structure & Style o Why does the story use humor and satire rather than taking a more serious tone? o How does the author balance criticism of performative activism with empathy for well-meaning people? o What purpose do the food descriptions serve beyond their literal meaning? 2. Narrative Choices o Why does the story focus on a white protagonist learning about her own behavior rather than on the experiences of people of color? o How does the author use specific incidents (like the diversity gala, the cooking classes) to illustrate larger themes? o What is the significance of ending with an epilogue showing the long-term impact of Sarah's change? Group Discussion Activities 1. Text Analysis o Compare Sarah's social media posts from the beginning of the story with her actions at the end. What has fundamentally changed? o Identify moments where characters could have responded with anger to Sarah but chose not to. Why might the author have made this choice? 2. Real-World Connections o Bring examples of performative activism from current events. How do they compare to Sarah's behavior? o Discuss examples of genuine allyship you've witnessed. What made them authentic rather than performative? 3. Personal Reflection o Share instances where you've caught yourself being performative rather than genuine in your attempts to do good. o Discuss what "doing the real work" means in your own context and community. Writing Prompts 1. Write a scene from Dr. Chen's perspective during one of her early encounters with Sarah. 2. Compose one of Sarah's apologetic emails to someone she wronged. 3. Draft a social media post that the "new" Sarah might write about genuine community building. Final Reflection Consider how this story might influence your own approach to social justice work and online activism. What lessons from Sarah's journey might you apply to your own life?

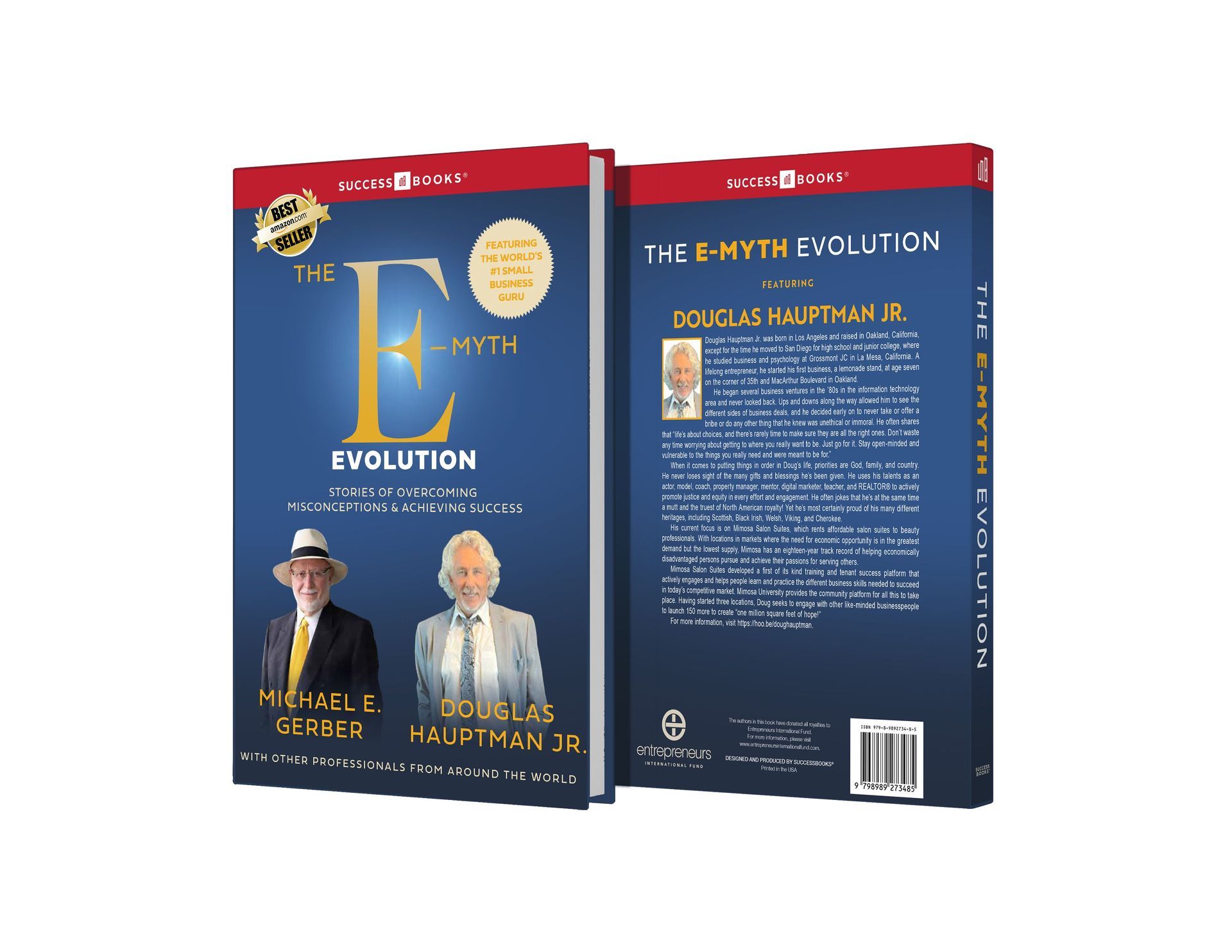

Here is my chapter in the Best Selling book E-Myth Evolution! I was talking to my chiropractor like he was my therapist. As he twisted and cracked and released, I poured out my business woes. I was starting to buckle under the weight of my responsibilities, and it was all palpable, there in the back of my neck. He pounded on my shoulders. “You’re all locked up,” he said. I had recently opened the doors on my most recent business venture: Mimosa Salon Suites. 10,000 square feet of office space in Conyers, Georgia that had been converted into individual salon suites to be rented by beauty professionals. The goal of the business was to provide a landing pad and a place to grow for lower income business owners, primarily black women, most of them in their mid-twenties to mid-forties. Our occupancy was full, we were doing well and growing, but I was single-handedly managing every aspect of the business. It felt to me like everything in the company relied on me. When I tried to outsource it was ineffective, because no one seemed to care as much as I did or perform to my standards. I wasn’t sure what to do, but I knew if something didn’t change, I wouldn’t be able to sustain. My chiropractor looked at me and my hiked-up shoulders, and he presented me with a gift. “Here,” he said. “Read this.” He handed me his phone. On it was a book, Awakening the Entrepreneur Within: How Ordinary People Can Create Extraordinary Companies, by Michael Gerber. I left his office, my back feeling much better, and ordered the book as soon as I returned home. I should back up for a moment and tell you that I’ve always been an entrepreneur. I started at the age of seven, with a lemonade stand on the corner of 35th and MacArthur Boulevard in Oakland, California where I grew up. I chose 35th and MacArthur because it was on one of the busiest corners, across the street from a bus stop. Even at seven I knew a thing or two about supply and demand. I grew up, and in my early adulthood I caught the wave of the technology boom of the 1980s. I ran a company that sold microprocessors and semiconductors to some of the biggest computer manufacturers of the day. It was good business, but not great for my soul, and was eventually pulled out from underneath me in a hostile takeover. From there, I moved into marketing, and then to real estate which is where I germinated and eventually built the idea that became Mimosa Salon Suites. I was no beginner, and I’d done plenty of things right, but it wasn’t until I read Awakening that I realized how much I was still doing wrong. I had built a business on my own faltering back. I hadn’t yet created the systems or innovations that would allow me to step out from under all the daily tasks and truly begin to grow. I’ve always been a reader, and a self-taught man, so I began to implement Michael Gerber’s lessons immediately. E-Myth had changed my mind set in a single reading, but it was just the beginning of a larger shift. Like any transformative book or set of ideas, it was a catalyst rather than an endpoint. I went on the read E-Myth Mastery; The Seven Essential Disciplines for Building a World-Class Company, next. Others followed. What I understood right away is that I would need to learn and become an expert in all the different areas of my business. The Seven Essential Disciplines became a blueprint for how I could begin to have true mastery over this thing that I was building. I did what I always do: I began. I put one foot in front of the other. The spirit that kept me hawking cups of lemonade when I was seven was the same spirit that I brought to growing my business: “I’m not sure if this is going to work, but I’m going to give it a try.” It’s the song of the self-made person. It doesn’t matter if you’re the smartest or the fastest, if you can stay the course and stick it out, even when things get tough, you’re going to go the distance. I dug in. I started studying and researching and learning. I read every other E-Myth book I could get my hands on, as well as many other books on the areas I needed to grow into. As I progressed, I found two key lessons to be the most pivotal in taking my business from one 10,000 square foot location to three locations making almost $1,000,000 a year in revenue. Lesson One I needed to have a mission far larger than the success of the business, and after working through the exercises in Part One of E-Myth Mastery I came up with our mission statement “One Million Square Feet of Hope!” I’m no stranger to missions. When I was young and on the heady cutting-edge of personal computers, I tasted a kind of financial success I’d never known before. I had tens of millions of dollars in contracts, and I was living the high life, in every sense of the word. Though it had its thrills, there was an emptiness to what I was doing. I, and everyone around me, was motivated entirely by the almighty dollar. I was rich, but I wasn’t sleeping well at night. I understood, without anyone ever telling me, that the road I was on might lead me to a vast fortune, but it wouldn’t take my soul anywhere but down. It was when I left that world, and started building websites as a contractor that the first seeds of mission were planted. I still remember the church service I went to, just months before I started Mimosa Salon Suites. I was making in the high six-figures at the time, and the sermon was about how those of us with wealth needed to find ways to give back. It hit me hard. After leaving the world of big tech, I had encountered my spiritual self and developed a deeply personal relationship with God. I understood how much of the health and goodness of my current life was due to that union, so I took the sermon seriously: I was supposed to be a good steward, using what I’d been given to make the world a better place. I sat in the pew and made the decision. I would find a way to do something sustainable, that would provide a service to people in the world who needed help and support. Reading E-Myth, all those many years later, reminded me of the importance of my original mission. The goal of your business can’t be the profit. If it is, you’ll lose sight of what matters and quite possibly who you are and what you stand for. The goal of your business must be the community you’ll serve, the changes you will bring, and the hearts you plan to set aflame. I wasn’t just renting salon space; I was helping people become entrepreneurs. With that in mind, I began to focus on all the ways in which we could support our tenants so that if they wanted to, they could grow into business owners themselves. Today, every new tenant in any of our Salon Suites locations gets a free copy of Awakening the Entrepreneur Within. We’ve created online courses about business development that we offer free of charge to our tenants. Instead of trying to trap people in a lease, we have a seven-day cancellation policy. We also offer a three-week break from rent for maternity leave, one week for bereavement, and prorated rent for any kind of hospital stay. We’re one of the only in our industry with these kinds of policies in place. If our mission was pure profit, we would act like ninety-nine percent of the other landlords out there and hold tenants captive until they finally managed to squeak out of their grasp. This kind of predatory practice, at its core, just isn’t good for business. It turns out that being compassionate, and just doing the right thing, is. The men and women who rent from us are fiercely independent and quite motivated. They’re sick of being gouged renting a chair at a larger salon, where they have no freedom, and no right to the profits of any products that they sell. They want something that they can call their own, and that’s what we provide for them. In most cases, when one of our tenants leave, it’s because they are starting their own salon or shop. Most landlords hate the move out notice from a tenant, but for me it’s cause for celebration. Many of these people have become an extension of my family. I’ve coached them when they’ve asked, supported their aspirations in whatever way I can, and watching them walk out the door toward their own business venture fills me with pride. Not that I did any of it, mind you, it’s all their own drive and determination that got them there—but it always feels like an honor to have provided them with a place to start. And, because our practices are built on compassionate, support, and growth; there’s always another tenant ready to fill their spot. Lesson Two Awakening will get your mind set in the right direction, and Mastery will set you on the path to growth. As I began to learn about all the disparate areas of the business, simultaneous to building our mission, it became clear that understanding the ins and outs of the business was the only way out of the trap of “doing it all myself.” I taught myself sales and marketing and operations. I learned the needs and pain points of our tenants. I figured out what was missing, and then found the people and processes to fill those gaps. The results of this work were undeniable. We went from $200,000 in revenue to $950,000 in revenue over several years, maintaining a healthy fifty percent margin with the eighty-two units we run at 100% occupancy. Because of the systems now in place, we have our eye on big growth by way of franchising. Because of my tech background, I understood that we had to leverage technology in every way we could to create systems and processes that work. For time and project management we use Basecamp. For surveys we use SurveyMonkey. For social media planning and scheduling we use Hootsuite. Most recently, we’ve begun adopting the AI strategies from AI marketing platform, deal.ai. You can’t have a true enterprise if you don’t have enterprise systems in place. I also made sure that we had a built-in innovation loop in place. That means that innovation is an active, trackable part of the systems of the company. We aren’t just maintaining the status quo, we are constantly evolving so that at any given point in time, we are at least a step or two ahead of our peers and competitors. The COVID 19 pandemic was a great example of this. By February of 2020, I saw the writing on the wall. I was one of the first business owners in Atlanta to write the initial medical protocols for the pandemic. These later got woven into the state policy. I understood that it was our job to create an environment where people both felt safe and were safe. We accomplished it, and because of that planning and innovating, Mimosa Salon Suites were able to stay open throughout most of the entire pandemic. These are just some of the ways in which building true mastery will help you survive. Very few businesses do. Creating a business plan that reflects your values and building your own deep understanding of your organization and its systems, will separate you as a survivor, rather than just another flash-in-the-pan. As I learned and stretched, I documented every part of the business we were building. At this point, many years into this learning, I am confident that if I disappeared tomorrow my business could run successfully without me. That’s how ingrained and teachable every process is. I’ve also created a succession plan, and the youngest of my four children, my daughter Mali, is set to learn the business and one day take over. To my great pride and joy. This groundwork also supports our next step, franchising Mimosa Salon Suites. My “One Million Square Feet of Hope,” dream is to see a Salon Suites in every city in the country—wherever there is need—so that aspiring salon owners can have a place to build their own future. I’ve seen the impact we’ve had on the community here in East Metro Atlanta, and I know the need is deep and far-reaching. As we execute our franchise plan and wait for the ideal economic timing (another lesson of mastery), I’m busy growing and coaching. I’ve realized that I, as the face of the business, am an integral part of its continued success. A system of my own. So, I have prioritized my health and well-being, to grow right along with the business. I believe that by building my own brand, I can reach beyond my tenants and colleagues, to touch the hearts of other business owners and entrepreneurs. Especially those of my own generation. Because getting older doesn’t have to mean sitting in a chair on your porch, watching the world go by. Aging is not what it once was. I’m sixty-three years old, and I have no plans to slow down anytime soon. Michael Gerber, now eighty-seven himself, often gets asked if he’s going to retire. His answer is always no. Why would he? If he’s taught us anything, it’s that when you’re building something great, living your dream, and aligned with a mission larger than yourself, there is no need to stop. If you’re lit up with what you’re doing, all you want to do is keep it going. As I get older, my mission comes into even sharper focus. I’m here to build bridges for aspiring entrepreneurs. I’m here to encourage and to coach and create opportunities. But more than anything, I’m here to love. To find grace and compassion and forgiveness wherever it lives. So many of us look to our differences instead of what we have in common. Creating Mimosa Salon Suites has shown me how alike we all really are, and though I may not have known it at the time, it was love that motivated the creation of Mimosa Salon Suites from the very beginning, and love that will keep it going, growing, and innovating. Once you find that—the love that powers your goals—then you know you’re on the right path. Read more inspirational stories from 11 other entrepreneurs! Buy the Best Selling book E-Myth Evolution on Amazon.com today! Thanks for reading.